Public benefit

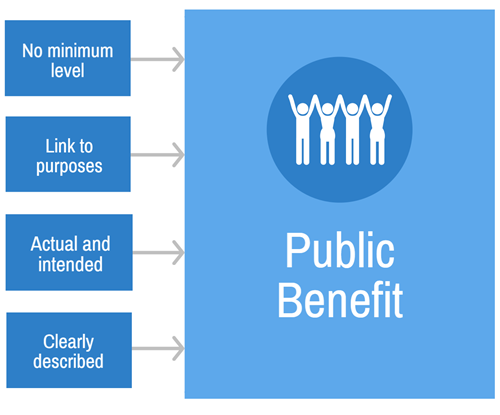

To pass the charity test an organisation must:

- have only charitable purposes, and

- have activities which provide public benefit in Scotland or elsewhere.

To see whether an organisation provides public benefit or (in the case of applicants) intends to provide public benefit, we look at what it does or plans to do to achieve its charitable purposes. Having charitable purposes will not on its own mean that the charity test is met; an organisation’s activity must also provide public benefit.

What is public benefit?

In general, public benefit is the way that a charity makes a positive difference to the public. Not everything that is of benefit to the public will be charitable. Public benefit in a charitable sense is only provided by activities which are undertaken to advance an organisation’s charitable purposes.

Charities can provide public benefit in many different ways and in differing amounts.

Some benefits are easy to understand and measure. If your organisation sets out to help people with a certain type of disease, it is easy to point to the benefit its activities provide in relieving sufferers’ symptoms or in curing them. It is more difficult to measure the benefits of other types of charities, for example, a society preserving a part of our heritage, but that does not mean that there is no benefit.

Sometimes there is benefit to the public as a whole from a charity’s activities as well as to the people they are directly meant for. An example would be activities that promote literacy and health awareness among women in developing countries. As well as directly benefiting the women concerned, there is indirect benefit to the public in those societies by improving public health, especially in children.

There is no specific level of benefit that a charity must provide; many charities operate on a small scale or in small communities but are still able to show that they do provide public benefit.

However, an organisation must actively provide benefit or (in the case of applicants) intend to provide it. In general, if a charity does nothing for a prolonged period, it is unlikely to be providing public benefit, and this may result in it failing the charity test. There are some exceptions where this principle does not apply. We call these ‘inactive charities’.

Inactive charities

One type of inactive charity is where a charity is set up to act if a particular event occurs in the future, and where public benefit is provided because the charity is there ‘just in case’.

For example:

- a charity is set up to relieve the needs of those who might be made homeless by flooding in a flood-prone area of Scotland – there may be no floods and therefore no activity for several years, but the existence of the charity allows prompt relief should a flood occur.

Another type of inactive charity is a ‘legacy’ charity:

- where one charity is replaced or taken over by another, the charity which has been taken over continues purely to receive legacies and pass them to the new charity – there may be long periods where no money is received or transferred, but the ‘legacy’ charity provides benefit by making sure that donations reach the right destination.

Where an inactive charity remains on the Register, it will still need to meet all the requirements of being a charity. In particular it must:

- meet the charity test

- have charity trustees who comply with all the charity trustee duties

- comply with annual monitoring: preparing and submitting accounts, trustees’ annual report and the Online annual return.

A legacy charity should consider if its governing document needs to be changed. The purposes and powers of the old charity will reflect what it was originally set up to achieve – for instance they may not cover transferring legacy funds to the new charity, and may need to be changed. Other aspects of the governing document may also need to be amended if they no longer fit the new role of the legacy charity, for example the provisions about membership and the holding of meetings.

To make changes to the charity’s purposes you will need our prior consent. Other changes should be made in line with the requirements of your charity’s current governing document and then notified to OSCR. See our guidance on changing charitable purposes for more information.

What is benefit?

The ‘benefit’ that charities provide can take many different forms. Some benefits may be clear and measurable. For example, where a charity relieves a person’s sickness or financial hardship, any improvements in the person’s health or financial circumstances can be measured. These benefits could be described as ‘tangible’.

On the other hand, ‘intangible’ benefits may be more difficult to measure, but should still be identifiable. These can include the benefits of education or religion, or promoting appreciation of historic buildings. Both tangible and intangible benefits are taken into account when we assess public benefit.

What does public mean?

The ‘public’ part of public benefit doesn’t necessarily refer to the general public as a whole. Some charities will potentially benefit everyone in a community. For example, a charity, which has recreational purposes where activities are open to all. However, most charities will have limits on who they benefit, and some charities will only benefit a small number of people.

How many people a charity benefits and who they are will depend on the charitable purposes set out in the governing document: most charities are established to benefit a particular group. For example, many charities benefit children in general, while others are established to benefit children of a certain age or those with specific needs.

How does the benefit link to charitable purposes?

Generally, to be taken into account in the assessment of public benefit, an organisation’s activities must be clearly intended to advance its charitable purposes.

Where an organisation carries out some activity that is not directly related to or connected with its purposes, any benefit from that activity will not be taken into account in our assessment of public benefit. However, if the activity is genuinely incidental (a by-product of its main activities), then it will not be a problem in terms of the public benefit requirement or the organisation’s duty to act within its charitable purposes.

For example, a community theatre group with the purpose to advance the arts also collects cash donations for a local hospice in the intervals of its shows. This activity clearly doesn’t advance the arts, but does not adversely affect the overall picture of the group’s public benefit.

If charity trustees feel that their charity’s activities no longer reflect the purposes in its governing document, then they might decide to seek our consent to change the charitable purposes. It is good practice to review a charity’s governing document on a regular basis to make sure that it is still accurate and relevant for the charity.

How does a charity demonstrate that it provides public benefit?

This is a key part of being a charity. Charities must describe the work that they do, and their achievements, in their Trustees Annual Report. This information allows the public to see how much public benefit arises from a charity’s activities; it is also important because it requires all charity trustees to review their purposes, activities and achievements annually.

Our Guidance on the individual charitable purposes has more information on what activities may provide public benefit in the advancement of each purpose.

How do we assess public benefit?

To be on the Scottish Charity Register, an organisation must have only charitable purposes and provide public benefit.

In terms of the 2005 Act, to decide whether an organisation provides public benefit or (in the case of applicants) intends to provide public benefit, the following elements must be considered:

- The comparison between the benefit to the public from an organisation’s activities; and

- any disbenefit (which is interpreted as detriment or harm) to the public from the organisation’s activities

- any private benefit (benefit to anyone other than the benefit they receive as a member of the public).

- The other factor that we must take into account in reaching a decision on public benefit is whether any condition an organisation imposes on obtaining the benefit it provides is unduly restrictive. This includes fees and charges. See undue restrictions for more information.

While considering these factors, we make a judgement on the whole picture of public benefit in the organisation being looked at. We do this based on all the facts and circumstances applying to the organisation.